Expanding How We Think About Early Warnings and Disaster Preparedness

By Dr. Lily Bui, PhD

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Department of Urban Studies & Planning

There is a Greek myth about a woman named Cassandra, who was cursed by the god Apollo to have the ability to see impending doom but the inability to persuade anyone around her to believe her prophecy. In the myth, she is able to see the fall of Troy, and yet is disregarded by those living in the city. Eventually, she descended into madness, unable to reconcile the futility of her visions. The “Cassandra syndrome” is named after this myth, used to describe valid alarms which are disbelieved. Former White House National Security Council Director Richard A. Clarke and UN senior diplomat R.P. Eddy write in their book about the Cassandra syndrome as it pertains to warnings of past catastrophes (i.e., Hurricane Katrina, Fukushima, the Great Recession, and the rise of ISIS):

“Today when someone is labeled a Cassandra, it’s commonly understood that they simply worry too much and are fatalistic, overly pessimistic or focus too much on the improbable downside, a Chicken Little rather than a prophet…[A] Cassandra should be someone whom we value, whose warnings we accept and act upon. We seldom do, however. We rarely believe those whose predictions differ from the usual, who see things that have never been, whose vision of the future differs from our own, whose prescription would force us to act now, perhaps changing the things we do in drastic and costly ways.”

Are city leaders the Cassandras of our time? Why do people heed some disaster warnings but completely seem to ignore others? Why does disaster preparedness sometimes fail to mitigate risk for people who are in harm’s way?

It may be because we — as municipal leaders, emergency managers, community leaders, insurance companies, and citizens — are thinking about warnings too narrowly. Most of the time, when we talk about warnings or warning systems, we’re talking about forecasting. This involves interpreting scientific and technical information about the environment into decisions and action for what to do. For example, forecasting during a hurricane involves an authority like the National Weather Service interpreting available weather models to predict wind speed, storm surge, and rainfall, and telling the media, emergency managers, and the general public how to respond appropriately. This is a good framework for preparedness, but by the time forecasting happens, especially in places where communities do not properly understand their own risk, the “early” warning is already too late.

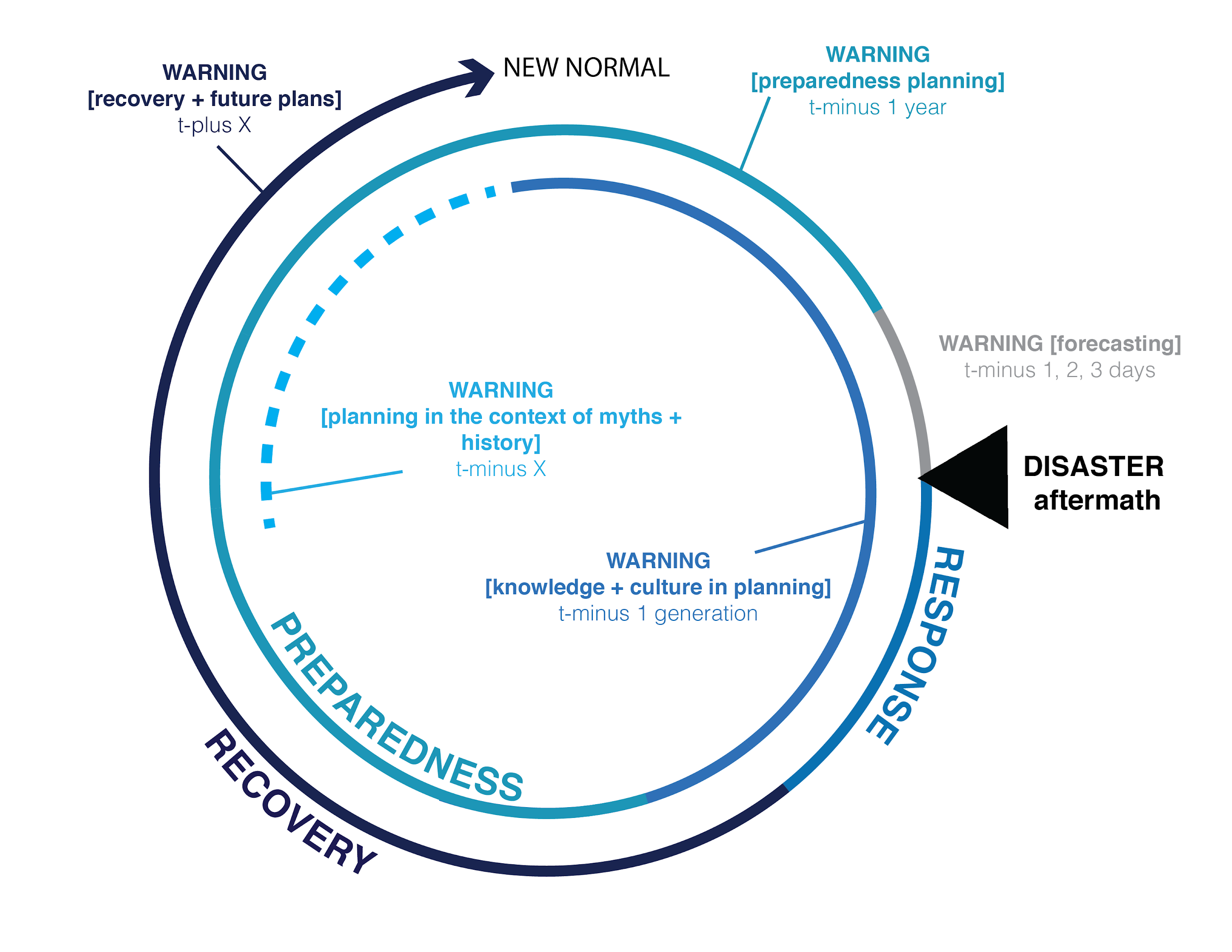

Below is another way to think about warnings. This is a much, much more expansive framework that doesn’t just look at forecasting — which happens in the few days, hours, or minutes before a disaster happens — but also further back and even forward in time. We’ve already talked about forecasting, pictured below in grey, which is a form of short-term warning. The other forms of longer-term warning allow city leaders to incorporate better long-term preparedness, knowledge and culture of risk, history, and future recovery plans into warning systems.

T-minus 1, 2, 3 days: forecasting. This is a short-term form of warning that encompasses the few days, hours, or minutes before a disaster is predicted to occur. The lead time before an event can either be shorter, such as for a tsunami, or longer, such as for sea-level rise. This is the time when the efficacy of preparedness planning is tested, when the strength of relationships between individuals and organizations is measured, and when the resilience of a community is revealed.

T-minus 1 year: preparedness planning. To look back within the year before a disaster event allows one to understand what planning measures or preparedness efforts may have existed (or not) before a disaster incident occurs. Were people aware of the potential of such an event? Would they have known what to do? Your city planners have much to do with this phase, as preparedness planning entails long-term engagement with communities to assess their risk, bolstering education and training opportunities for people to understand how to mitigate that risk, and liaising between institutions and governments to ensure each knows their role when disaster occurs.

T-minus 1 generation: knowledge and culture. To look back t-minus one generation from the incident may help one better understand where risk knowledge came from and how it was formed. Were there previous similar disasters that had occurred in the same area or region? Were stories passed down from one generation to the next about risk? City leaders are responsible for understanding how a culture of preparedness can be constructed through preparedness efforts. There are cultural factors and generational knowledge that contribute to the way that a society might come to understand risk, and preparedness efforts must be responsible for unearthing these.

T-minus X: preparedness in the context of myths and history. To look even further back in time, an analysis of t-minus X amount of time may help reveal more detailed insight about why a society’s social, cultural, political, and economic history may help explain some of its behaviors around certain types of risk. In designing better warning systems, we must dig into deep a place’s history. Some societies’ prior understanding of risk is rooted in a past that is not easily revealed at first blush, thus making behavioral change a greater challenge. It is the responsibility of disaster preparedness processes to bring these issues to light.

T-plus X: recovery and future plans. To look at t-plus X amount of time after a disaster incident occurs means to attempt to understand how post-disaster recovery efforts aspire to warn of future risk based on what came before. What should future communities and institutions be wary of when rebuilding? In what ways can individuals and groups be better prepared for disasters yet to come? How should these concerns be reflected in plans and policy? Who gets to decide this, and who gets to be part of the decision making process? City leaders must help usher societies that have suffered through disasters toward a “new normal” that is more sustainable and resilient than the past.

So, given all of these options for short- and long-term warning, what does this actually look like in practice? Take a look at the chart below to see examples from Hawaii and Puerto Rico of how preparedness, local knowledge and culture, history, and future recovery efforts can feed into how warnings are designed and implemented.

| Timing | Disaster Cycle Phase | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| t-minus 1 year | Preparedness | Education and training opportunities from the National Disaster Preparedness Training Center delivered on O’ahu and Puerto Rico in months leading up to Hurricanes Maria and Lane. |

| t-minus 1 generation | Culture Local knowledge | Individuals’ stories of hurricanes that they have lived through, passed onto younger generations. |

| t-minus X | History | Evidence that hurricanes and storms were part of Hawaiian and Puerto Rican folklore and history. |

| t-plus X | Recovery Future plans | Recovery or resilient planning efforts that include documentation of damage from past storms in order to set a baseline for future plans. |

Warning systems are not simply a tool for reducing risk. Designing them is a long-term process that helps communities understand their risk over time and respond to it appropriately when it is most important to do so. How does your community think about preparedness and warning? Are you taking into account the longer-term types of warning?

Dr. Lily Bui received her PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Department of Urban Studies & Planning where she specializes in early warnings, disaster recovery, and humanitarian assistance.